83 Eukaryotic Post-transcriptional Gene Regulation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Understand RNA splicing and explain its role in regulating gene expression

- Describe the importance of RNA stability in gene regulation

RNA is transcribed, but must be processed into a mature form before translation can begin. This processing that takes place after an RNA molecule has been transcribed, but before it is translated into a protein, is called post-transcriptional modification. As with the epigenetic and transcriptional stages of processing, this post-transcriptional step can also be regulated to control gene expression in the cell. If the RNA is not processed, shuttled, or translated, then no protein will be synthesized.

RNA Splicing, the First Stage of Post-transcriptional Control

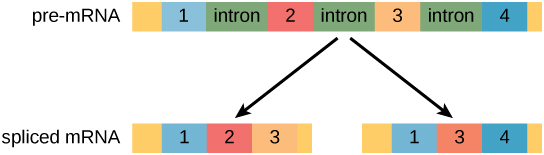

In eukaryotic cells, the RNA transcript often contains regions, called introns, that are removed prior to translation. The regions of RNA that code for protein are called exons. ((Figure)). After an RNA molecule has been transcribed, but prior to its departure from the nucleus to be translated, the RNA is processed and the introns are removed by splicing. Splicing is done by spliceosomes, ribonucleoprotein complexes that can recognize the two ends of the intron, cut the transcript at those two points, and bring the exons together for ligation.

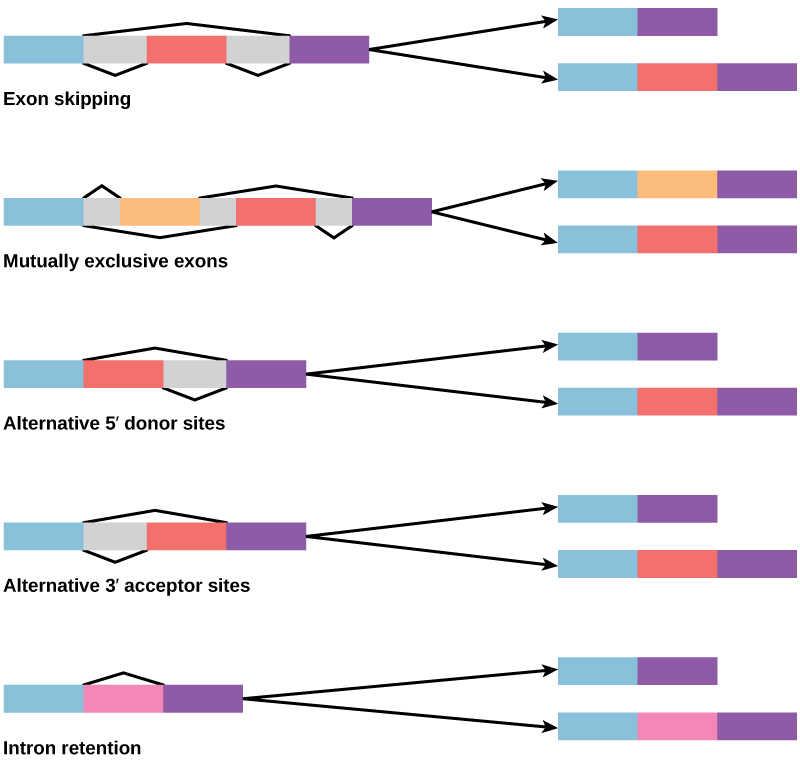

Alternative RNA SplicingIn the 1970s, genes were first observed that exhibited alternative RNA splicing. Alternative RNA splicing is a mechanism that allows different protein products to be produced from one gene when different combinations of exons are combined to form the mRNA ((Figure)). This alternative splicing can be haphazard, but more often it is controlled and acts as a mechanism of gene regulation, with the frequency of different splicing alternatives controlled by the cell as a way to control the production of different protein products in different cells or at different stages of development. Alternative splicing is now understood to be a common mechanism of gene regulation in eukaryotes; according to one estimate, 70 percent of genes in humans are expressed as multiple proteins through alternative splicing. Although there are multiple ways to alternatively splice RNA transcripts, the original 5′-3′ order of the exons is always conserved. That is, a transcript with exons 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 might be spliced 1 2 4 5 6 7 or 1 2 3 6 7, but never 1 2 5 4 3 6 7.

How could alternative splicing evolve? Introns have a beginning- and ending-recognition sequence; it is easy to imagine the failure of the splicing mechanism to identify the end of an intron and instead find the end of the next intron, thus removing two introns and the intervening exon. In fact, there are mechanisms in place to prevent such intron skipping, but mutations are likely to lead to their failure. Such “mistakes” would more than likely produce a nonfunctional protein. Indeed, the cause of many genetic diseases is abnormal splicing rather than mutations in a coding sequence. However, alternative splicing could possibly create a protein variant without the loss of the original protein, opening up possibilities for adaptation of the new variant to new functions. Gene duplication has played an important role in the evolution of new functions in a similar way by providing genes that may evolve without eliminating the original, functional protein.

Question: In the corn snake Pantherophis guttatus, there are several different color variants, including amelanistic snakes whose skin patterns display only red and yellow pigments. The cause of amelanism in these snakes was recently identified as the insertion of a transposable element into an intron in the OCA2 (oculocutaneous albinism) gene. How might the insertion of extra genetic material into an intron lead to a nonfunctional protein?

Visualize how mRNA splicing happens by watching the process in action in this video.

Control of RNA Stability

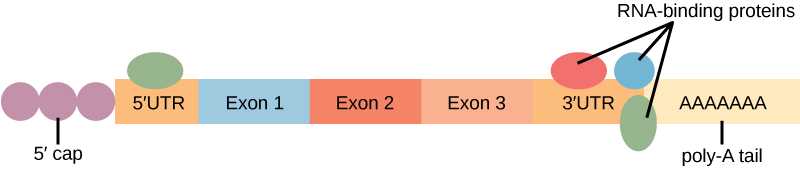

Before the mRNA leaves the nucleus, it is given two protective “caps” that prevent the ends of the strand from degrading during its journey. 5′ and 3′ exonucleases can degrade unprotected RNAs. The 5′ cap, which is placed on the 5′ end of the mRNA, is usually composed of a methylated guanosine triphosphate molecule (GTP). The GTP is placed “backward” on the 5′ end of the mRNA, so that the 5′ carbons of the GTP and the terminal nucleotide are linked through three phosphates. The poly-A tail, which is attached to the 3′ end, is usually composed of a long chain of adenine nucleotides. These changes protect the two ends of the RNA from exonuclease attack.

Once the RNA is transported to the cytoplasm, the length of time that the RNA resides there can be controlled. Each RNA molecule has a defined lifespan and decays at a specific rate. This rate of decay can influence how much protein is in the cell. If the decay rate is increased, the RNA will not exist in the cytoplasm as long, shortening the time available for translation of the mRNA to occur. Conversely, if the rate of decay is decreased, the mRNA molecule will reside in the cytoplasm longer and more protein can be translated. This rate of decay is referred to as the RNA stability. If the RNA is stable, it will be detected for longer periods of time in the cytoplasm.

Binding of proteins to the RNA can also influence its stability. Proteins called RNA-binding proteins, or RBPs, can bind to the regions of the mRNA just upstream or downstream of the protein-coding region. These regions in the RNA that are not translated into protein are called the untranslated regions, or UTRs. They are not introns (those have been removed in the nucleus). Rather, these are regions that regulate mRNA localization, stability, and protein translation. The region just before the protein-coding region is called the 5′ UTR, whereas the region after the coding region is called the 3′ UTR ((Figure)). The binding of RBPs to these regions can increase or decrease the stability of an RNA molecule, depending on the specific RBP that binds.

RNA Stability and microRNAs

In addition to RBPs that bind to and control (increase or decrease) RNA stability, other elements called microRNAs can bind to the RNA molecule. These microRNAs, or miRNAs, are short RNA molecules that are only 21 to 24 nucleotides in length. The miRNAs are made in the nucleus as longer pre-miRNAs. These pre-miRNAs are chopped into mature miRNAs by a protein called Dicer. Like transcription factors and RBPs, mature miRNAs recognize a specific sequence and bind to the RNA; however, miRNAs also associate with a ribonucleoprotein complex called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The RNA component of the RISC base-pairs with complementary sequences on an mRNA and either impede translation of the message or lead to the degradation of the mRNA.

Section Summary

Post-transcriptional control can occur at any stage after transcription, including RNA splicing and RNA stability. Once RNA is transcribed, it must be processed to create a mature RNA that is ready to be translated. This involves the removal of introns that do not code for protein. Spliceosomes bind to the signals that mark the exon/intron border to remove the introns and ligate the exons together. Once this occurs, the RNA is mature and can be translated. Alternative splicing can produce more than one mRNA from a given transcript. Different splicing variants may be produced under different conditions.

RNA is created and spliced in the nucleus, but needs to be transported to the cytoplasm to be translated. RNA is transported to the cytoplasm through the nuclear pore complex. Once the RNA is in the cytoplasm, the length of time it resides there before being degraded, called RNA stability, can also be altered to control the overall amount of protein that is synthesized. The RNA stability can be increased, leading to longer residency time in the cytoplasm, or decreased, leading to shortened time and less protein synthesis. RNA stability is controlled by RNA-binding proteins (RPBs) and microRNAs (miRNAs). These RPBs and miRNAs bind to the 5′ UTR or the 3′ UTR of the RNA to increase or decrease RNA stability. MicroRNAs associated with RISC complexes may repress translation or lead to mRNA breakdown.

Review Questions

Which of the following are involved in post-transcriptional control?

- control of RNA splicing

- control of RNA shuttling

- control of RNA stability

- all of the above

D

Binding of an RNA binding protein will ________ the stability of the RNA molecule.

- increase

- decrease

- neither increase nor decrease

- either increase or decrease

D

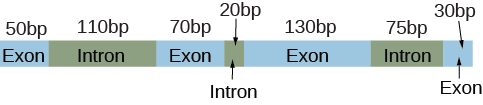

An unprocessed pre-mRNA has the following structure.

Which of the following is not a possible size (in bp) of the mature mRNA?

- 205bp

- 180bp

- 150bp

- 100bp

A

Alternative splicing has been estimated to occur in more than 95% of multi-exon genes. Which of the following is not an evolutionary advantage of alternative splicing?

- Alternative splicing increases diversity without increasing genome size.

- Different gene isoforms can be expressed in different tissues.

- Alternative splicing creates shorter mRNA transcripts.

- Different gene isoforms can be expressed during different stages of development.

C

Critical Thinking Questions

Describe how RBPs can prevent miRNAs from degrading an RNA molecule.

RNA binding proteins (RBP) bind to the RNA and can either increase or decrease the stability of the RNA. If they increase the stability of the RNA molecule, the RNA will remain intact in the cell for a longer period of time than normal. Since both RBPs and miRNAs bind to the RNA molecule, RBP can potentially bind first to the RNA and prevent the binding of the miRNA that will degrade it.

How can external stimuli alter post-transcriptional control of gene expression?

External stimuli can modify RNA-binding proteins (i.e., through phosphorylation of proteins) to alter their activity.

Glossary

- 3′ UTR

- 3′ untranslated region; region just downstream of the protein-coding region in an RNA molecule that is not translated

- 5′ cap

- a methylated guanosine triphosphate (GTP) molecule that is attached to the 5′ end of a messenger RNA to protect the end from degradation

- 5′ UTR

- 5′ untranslated region; region just upstream of the protein-coding region in an RNA molecule that is not translated

- Dicer

- enzyme that chops the pre-miRNA into the mature form of the miRNA

- microRNA (miRNA)

- small RNA molecules (approximately 21 nucleotides in length) that bind to RNA molecules to degrade them

- poly-A tail

- a series of adenine nucleotides that are attached to the 3′ end of an mRNA to protect the end from degradation

- RNA-binding protein (RBP)

- protein that binds to the 3′ or 5′ UTR to increase or decrease the RNA stability

- RNA stability

- how long an RNA molecule will remain intact in the cytoplasm

- untranslated region

- segment of the RNA molecule that is not translated into protein. These regions lie before (upstream or 5′) and after (downstream or 3′) the protein-coding region

- RISC

- protein complex that binds along with the miRNA to the RNA to degrade it