117 Characteristics of Protists

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Describe the cell structure characteristics of protists

- Describe the metabolic diversity of protists

- Describe the life cycle diversity of protists

There are over 100,000 described living species of protists, and it is unclear how many undescribed species may exist. Since many protists live as commensals or parasites in other organisms and these relationships are often species-specific, there is a huge potential for protist diversity that matches the diversity of their hosts. Because the name “protist” serves as a catchall term for eukaryotic organisms that are not animal, plant, or fungi, it is not surprising that very few characteristics are common to all protists. On the other hand, familiar characteristics of plants and animals are foreshadowed in various protists.

Cell Structure

The cells of protists are among the most elaborate of all cells. Multicellular plants, animals, and fungi are embedded among the protists in eukaryotic phylogeny. In most plants and animals and some fungi, complexity arises out of multicellularity, tissue specialization, and subsequent interaction because of these features. Although a rudimentary form of multicellularity exists among some of the organisms labelled as “protists,” those that have remained unicellular show how complexity can evolve in the absence of true multicellularity, with the differentiation of cellular morphology and function. A few protists live as colonies that behave in some ways as a group of free-living cells and in other ways as a multicellular organism. Some protists are composed of enormous, multinucleate, single cells that look like amorphous blobs of slime, or in other cases, like ferns. In some species of protists, the nuclei are different sizes and have distinct roles in protist cell function.

Single protist cells range in size from less than a micrometer to three meters in length to hectares! Protist cells may be enveloped by animal-like cell membranes or plant-like cell walls. Others are encased in glassy silica-based shells or wound with pellicles of interlocking protein strips. The pellicle functions like a flexible coat of armor, preventing the protist from being torn or pierced without compromising its range of motion.

Metabolism

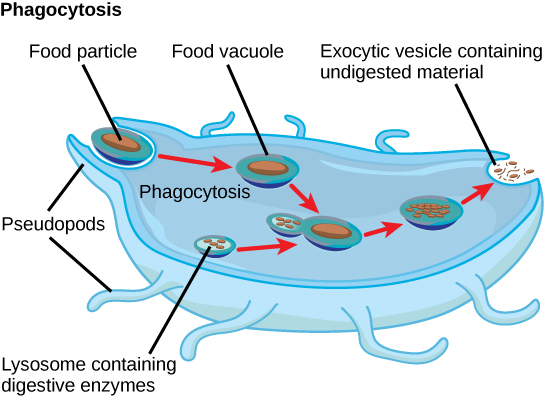

Protists exhibit many forms of nutrition and may be aerobic or anaerobic. Those that store energy by photosynthesis belong to a group of photoautotrophs and are characterized by the presence of chloroplasts. Other protists are heterotrophic and consume organic materials (such as other organisms) to obtain nutrition. Amoebas and some other heterotrophic protist species ingest particles by a process called phagocytosis, in which the cell membrane engulfs a food particle and brings it inward, pinching off an intracellular membranous sac, or vesicle, called a food vacuole ((Figure)). In some protists, food vacuoles can be formed anywhere on the body surface, whereas in others, they may be restricted to the base of a specialized feeding structure. The vesicle containing the ingested particle, the phagosome, then fuses with a lysosome containing hydrolytic enzymes to produce a phagolysosome, and the food particle is broken down into small molecules that can diffuse into the cytoplasm and be used in cellular metabolism. Undigested remains ultimately are expelled from the cell via exocytosis.

Subtypes of heterotrophs, called saprobes, absorb nutrients from dead organisms or their organic wastes. Some protists can function as mixotrophs, obtaining nutrition by photoautotrophic or heterotrophic routes, depending on whether sunlight or organic nutrients are available.

Motility

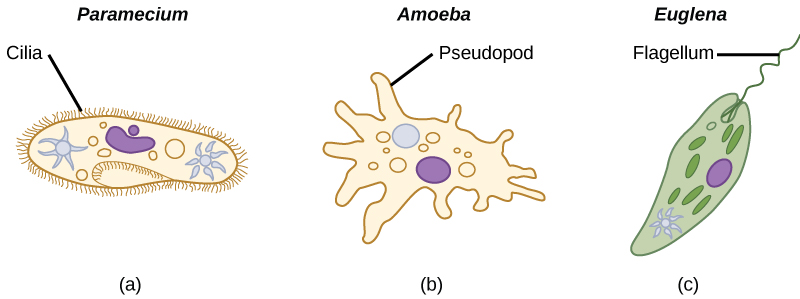

The majority of protists are motile, but different types of protists have evolved varied modes of movement ((Figure)). Some protists have one or more flagella, which they rotate or whip. Others are covered in rows or tufts of tiny cilia that they beat in a coordinated manner to swim. Still others form cytoplasmic extensions called pseudopodia anywhere on the cell, anchor the pseudopodia to a substrate, and pull themselves forward. Some protists can move toward or away from a stimulus, a movement referred to as taxis. For example, movement toward light, termed phototaxis, is accomplished by coupling their locomotion strategy with a light-sensing organ.

Life Cycles

Protists reproduce by a variety of mechanisms. Most undergo some form of asexual reproduction, such as binary fission, to produce two daughter cells. In protists, binary fission can be divided into transverse or longitudinal, depending on the axis of orientation; sometimes Paramecium exhibits this method. Some protists such as the true slime molds exhibit multiple fission and simultaneously divide into many daughter cells. Others produce tiny buds that go on to divide and grow to the size of the parental protist.

Sexual reproduction, involving meiosis and fertilization, is common among protists, and many protist species can switch from asexual to sexual reproduction when necessary. Sexual reproduction is often associated with periods when nutrients are depleted or environmental changes occur. Sexual reproduction may allow the protist to recombine genes and produce new variations of progeny, some of which may be better suited to surviving changes in a new or changing environment. However, sexual reproduction is often associated with resistant cysts that are a protective, resting stage. Depending on habitat of the species, the cysts may be particularly resistant to temperature extremes, desiccation, or low pH. This strategy allows certain protists to “wait out” stressors until their environment becomes more favorable for survival or until they are carried (such as by wind, water, or transport on a larger organism) to a different environment, because cysts exhibit virtually no cellular metabolism.

Protist life cycles range from simple to extremely elaborate. Certain parasitic protists have complicated life cycles and must infect different host species at different developmental stages to complete their life cycle. Some protists are unicellular in the haploid form and multicellular in the diploid form, a strategy employed by animals. Other protists have multicellular stages in both haploid and diploid forms, a strategy called alternation of generations, analogous to that used by plants.

Habitats

Nearly all protists exist in some type of aquatic environment, including freshwater and marine environments, damp soil, and even snow. Several protist species are parasites that infect animals or plants. A few protist species live on dead organisms or their wastes, and contribute to their decay.

Section Summary

Protists are extremely diverse in terms of their biological and ecological characteristics, partly because they are an artificial assemblage of phylogenetically unrelated groups. Protists display highly varied cell structures, several types of reproductive strategies, virtually every possible type of nutrition, and varied habitats. Most single-celled protists are motile, but these organisms use diverse structures for transportation.

Review Questions

Protists that have a pellicle are surrounded by ______________.

- silica dioxide

- calcium carbonate

- carbohydrates

- proteins

D

Protists with the capabilities to perform photosynthesis and to absorb nutrients from dead organisms are called ______________.

- photoautotrophs

- mixotrophs

- saprobes

- heterotrophs

B

Which of these locomotor organs would likely be the shortest?

- a flagellum

- a cilium

- an extended pseudopod

- a pellicle

B

Alternation of generations describes which of the following?

- The haploid form can be multicellular; the diploid form is unicellular.

- The haploid form is unicellular; the diploid form can be multicellular.

- Both the haploid and diploid forms can be multicellular.

- Neither the haploid nor the diploid forms can be multicellular.

C

The amoeba E. histolytica is a pathogen that forms liver abscesses in infected individuals. Its metabolic classification is most likely ______.

- Anaerobic heterotroph

- Mixotroph

- Aerobic phototroph

- Phagocytic autotroph

A

Critical Thinking Questions

Explain in your own words why sexual reproduction can be useful if a protist’s environment changes.

The ability to perform sexual reproduction allows protists to recombine their genes and produce new variations of progeny that may be better suited to the new environment. In contrast, asexual reproduction generates progeny that are clones of the parent.

Giardia lamblia is a cyst-forming protist parasite that causes diarrhea if ingested. Given this information, against what type(s) of environments might G. lamblia cysts be particularly resistant?

As an intestinal parasite, Giardia cysts would be exposed to low pH in the stomach acids of its host. To survive this environment and reach the intestine, the cysts would have to be resistant to acidic conditions.

Explain how the definition of protists ensures that the kingdom Protista includes a wide diversity of cellular structures. Provide an example of two different structures that perform the same function for their respective protist.

Protists are defined as any eukaryotes that do not fall into the Plantae, Fungi, or Animal Kingdoms. Since the unifying characteristics describe what they are NOT, rather than what they are, Protista can include almost any cellular/organism organization.

Possible examples of structure variety:

- Barrier to exterior world: cell wall, plasma membrane, pellicle

- Locomotion: flagella, cilia, pseudopodia

Glossary

- mixotroph

- organism that can obtain nutrition by autotrophic or heterotrophic means, usually facultatively

- pellicle

- outer cell covering composed of interlocking protein strips that function like a flexible coat of armor, preventing cells from being torn or pierced without compromising their range of motion

- phagolysosome

- cellular body formed by the union of a phagosome containing the ingested particle with a lysosome that contains hydrolytic enzymes